(Updated September 2014.) There are two things we ectomorphs often forget when getting into weightlifting. The first is that when we first start taking it seriously, well, we’re still novices. We can’t exactly be expected to perform lifts that require high degrees of athleticism – athleticism that we don’t necessarily have yet. This is off-putting, because we often desperately want to get bigger without being held up for months with all sorts of posture and mobility work. Luckily, we can develop mobility, strength, stability and power simultaneously with size. But we do need to learn how to move and lift right from the get-go though, otherwise we’re setting ourselves up for building an imbalanced body that looks funky, performs poorly and is vulnerable to injury.

The second thing we often forget is that we don’t have the same bone or muscle structures that most bodybuilders and powerlifters have. Most of those guys have highly specialized bodies, accomplished both through decades of training… and also their genetics. They’re often born with bodies that suit the lifts they do. Just like the tallest guys are drawn to basketball, weightlifters typically gravitate towards the lifts that they naturally excel at.

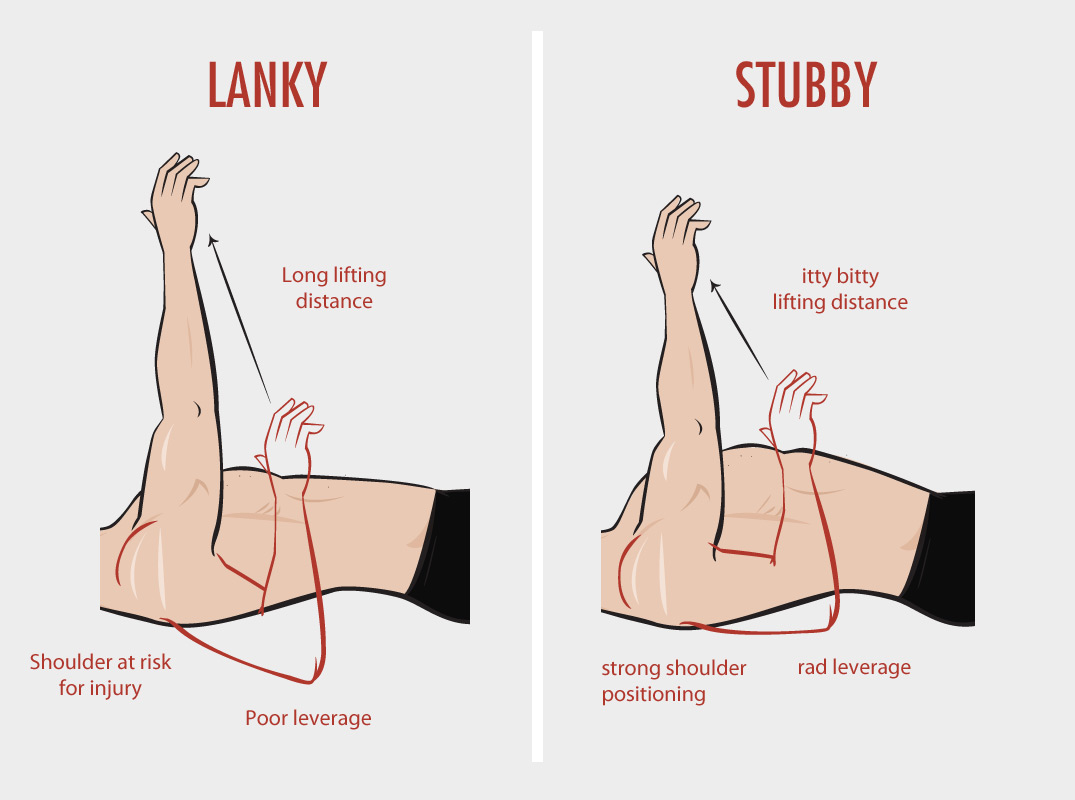

This means that the guys you’re watching do the bench press are often the worst ones to get your cues from. The lift is very different for them—they’ve got big muscle bellies, short thick bones, stubby limbs and barrel chests. We’ve often got long tendons, long slim bones, long lanky limbs and shallower rib cages.

Taking their cues is like asking a 7’2 guy how to dunk a basketball. He may very well say “uh just reach up and put it in.”

Overall we’re just longer people. We make better decathletes than shot-putters; better quarterbacks than linebackers. Hardly anything to be upset about—it’s not like thin guys can’t kick ass at athletics and build amazingly powerful bodies. We just need to take a different approach, and it’s not the approach you’d likely see the biggest guys in the gym taking.

But if we want to be strong muscular dudes we really do need to lift. Unlike many other body types, we can’t rely on our genetics or everyday physical activities to build us any muscle. (More on that here.) So let’s talk about lifting like ectomorphs so we can turn ourselves into big burly dudes.

Let’s start by digging into the three big lifts a little bit. Obviously these aren’t the only lifts you’d use, but usually they make a solid foundation to build a program around. They’ll also allow us to explain three of the five fundamental movement patterns (hip hinges, squats, upper body presses, upper body pulls, loaded carries).

Ectomorph Deadlifting

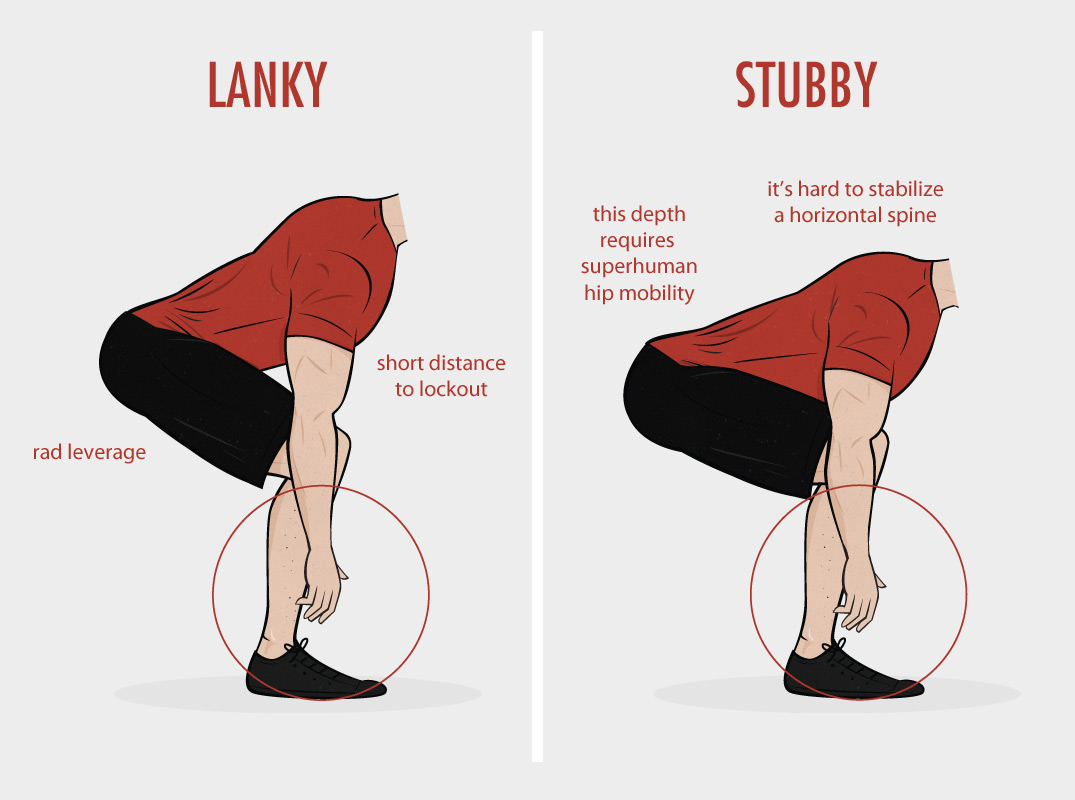

If you’re familiar with physics, you’ll intuitively know that our bone structure defines our lever lengths and affects the range of motion we lift weights through. This stuff plays a huge role in how much we can lift. A guy with gorilla-like arms can easily deadlift weight off the ground. He hardly needs to bend to grab the barbell and doesn’t need to lift the weight back up very high.

If you’re familiar with physics, you’ll intuitively know that our bone structure defines our lever lengths and affects the range of motion we lift weights through. This stuff plays a huge role in how much we can lift. A guy with gorilla-like arms can easily deadlift weight off the ground. He hardly needs to bend to grab the barbell and doesn’t need to lift the weight back up very high.

In physics terms that means he needs to exert a large force, sure, but since the distance travelledisn’t very far, there isn’t much “work” (force x distance) being done. Deadlifts are made even easier by having a short torso, which means there isn’t much spinal stabilization required. Plus, short lever lengths lead to rad leverage.

If an alligator-type guy were to attempt a deadlift he’d need to bend down ridiculously low because of his short little arms (also resulting in bad lifting mechanics) and then lift the weight through a huge range of motion—all while stabilizing an incredibly long torso. A huge amount of work is being done, a lot muscle surrounding the spine needs to be present to keep the spine stable, it requires impressive hip mobility, and that man needs to be wickedly strong to overcome really poor leverage.

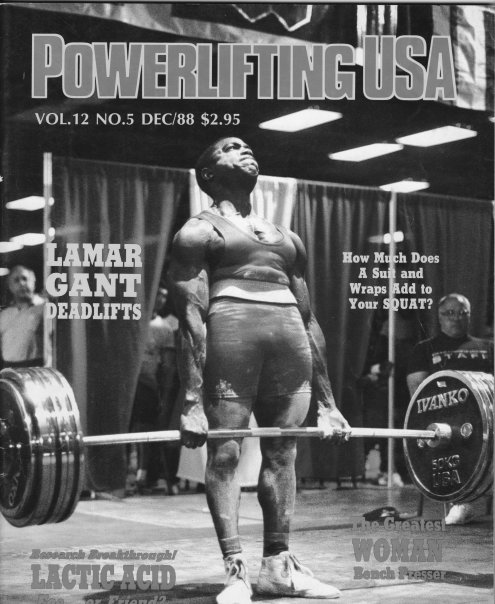

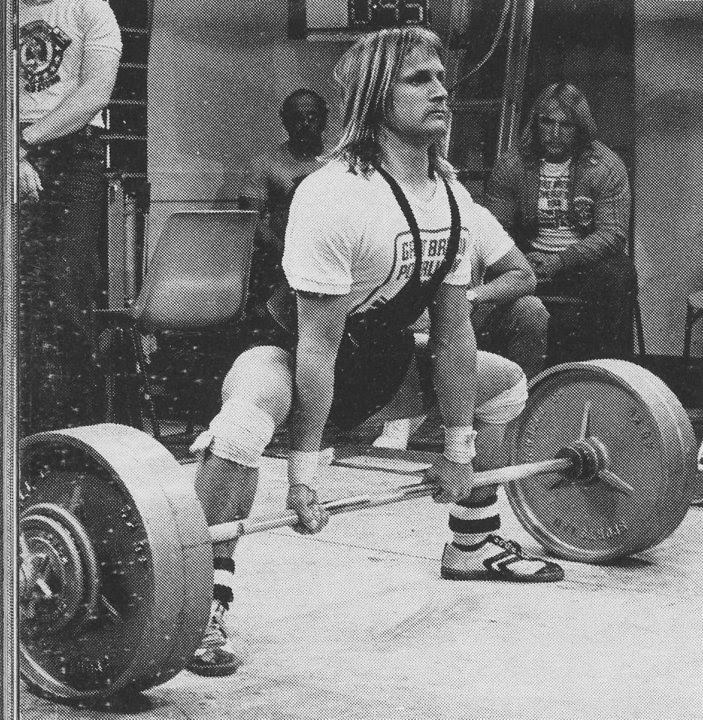

As such the world’s best deadlifters tend to look like Lamar Gant. Gant could deadlift over 600 pounds at a bodyweight of 120. Let me introduce you to the king of ectomorphs:

Most of us ectomorph have much longer torsos though, often leading us to believe that since we have long fragile spines we probably shouldn’t be deadlifting. That’s just asking for disaster, right? It makes sense that we should leave the deadlifting to the short muscular guys with short stable spines – the guys that don’t need to worry about popping a disk… right?

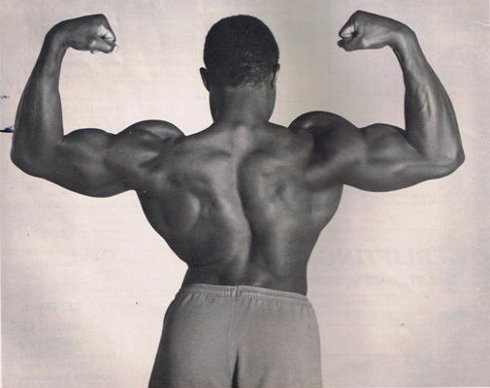

As guys with long fragile spines and with relatively little muscle protecting them, we, more than anyone, need to be doing lifts that build up stability in our torsos. That means building a stable core and packing huge slabs of muscle onto our lower and upper back. This will protect our long and precious spine.

And the best lift for developing a bullet-proof back, of course, is the deadlift. (Loaded carries are pretty good too.)

The last thing you want to do as an ectomorph is neglect strengthening your spine, build up a ton of muscle, get married while looking buff in your tux, get a little bit drunk at the wedding reception, go to carry your bombshell bride over the threshold… and throw out your still-fragile ecto-back.

If this sounds a little farfetched, just try to think up a scenario where you’d be lifting something and your back wouldn’t be involved at all. It’s kind of tricky. It hardly ever happens. Hell, you can’t even stand up and do a bicep curl without relying on your back for stability. And forget sweeping!

That’s why no amount of lower or upper body strength matters in the real world if you can’t transfer that load through your torso. You can’t squat big, deadlift big, overhead press, carry things, play sports, carry your lover around, etc.

The short stocky barrel-chested guys have stability in their torso naturally. We need to build it.

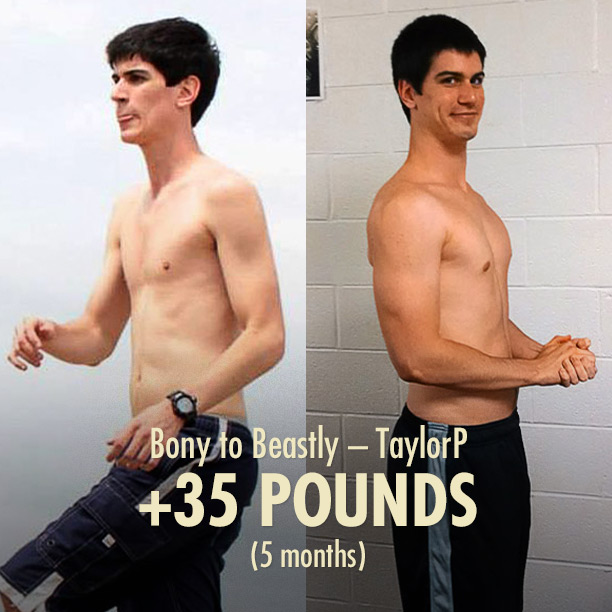

Many of us start out looking like crooked lollipops when viewed from the side—what with our long narrow bodies bent out of shape by years of postural/weightlifting neglect. Deads’ll fix that right up. Check out how much lower and upper back musculature one of our members, Brett, was able to build after 10 weeks of focusing on building up his posterior chain:

Even Lamar Gant, seemingly a rare breed of ectomorph with a short torso, actually isn’t as atypical as it first seems. He had a severe case of scoliosis growing up, hindering his back development and causing him a lot of problems. He decided to pursue weightlifting in an effort to correct his spinal curvature and strengthen the muscles surrounding his spine. So, far from being a genetic superhero, he entered the weightlifting arena skinny and with a crooked back.

His back is still crooked, but it’s now far from fragile:

The deadlift isn’t a lift reserved for the naturally strong of back, it’s really quite the opposite. If you assumed that ectomorph deadlifting was a recipe for disaster though don’t worry—I’m not going to make fun of you. Especially since you’re correct. We’ve got some work to do before we can dead like Gant.

For powerlifters, who need to follow a strict set of lifting regulations, the deadlift solution is to rock a really really wide stance, bringing their legs outside their arms. The “sumo” deadlift. This allows their torso to remain upright and means they don’t need to work as hard to stabilize it. It also shortens the range of motion and allows them to lift way heavier. Perfect for their sport. The downside is that instead of building up fearsome back strength, they build up fearsome quad strength.

Quads are cool, but if you’re already emphasizing squatting movement patterns elsewhere in your program you don’t need a second quad-dominant lift to focus on. It also doesn’t help us accomplish our main goal: a rock solid bulletproof back.

Luckily, since we aren’t powerlifters, we have the option of modding the lift by reducing the range of motion. So we take the barbell inside a squat rack, set it up the barbell raised up on the safety bars, and start with rack pulls. This keeps the dead an amazing exercise for building up back strength and stability, while also letting us safely lift heavy enough to stimulate some muscle growth. As you improve your mobility you can lower the bar lower and lower, requiring more and more hip mobility and back stability, until eventually you’re doing a full conventional deadlift—correctly and safely.

At that point your long arms become an advantage, and you should be able to hoist some pretty nice numbers. There’s no sense rushing right there though, as building up hip mobility and back strength is far more important than winning the powerlifting competition you aren’t in.

Ectomorph Bench Press

When it comes to pressing movements (overhead press, bench press, squat, etc) you want the opposite: a big barrel chest and stubby alligator-arms. Due to great lifting mechanics and a short range of motion, you’d hardly need to lower the weight at all and pressing it back up would be a breeze.

Us ectomorphs typically aren’t the most stubtastically built men, and we’re often spotted sporting a long lanky everything. This can make our first time on the bench a really frustrating experience, as the odds are totally stacked against us. We often awkwardly struggle to press tiny amounts of weight while we watch other guys rock it out smoothly and effortlessly.

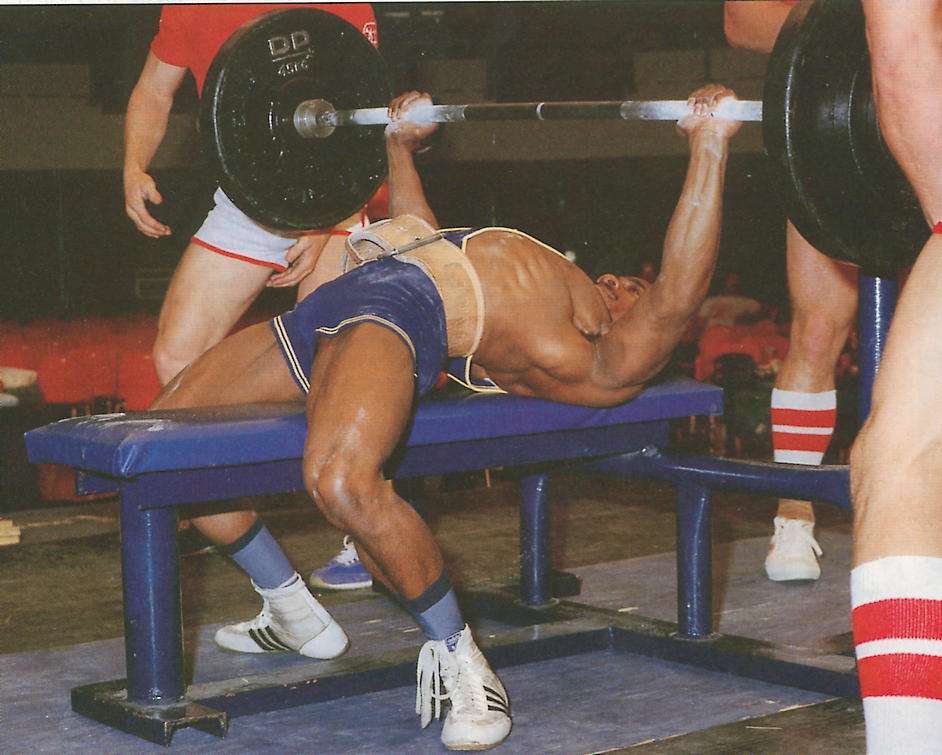

The problem isn’t that we suck at building muscle though—we don’t—the problem is that we’re trying to bang out routines designed by stocky people for stocky people. Lamar Gant, the ectomorph deadlifting king, was also able to break a world record with his bench press despite having the worst possible physique for it. If he can do it we sure as hell can.

When it comes to the bench press most powerlifters curve their spine to all hell to shorten the range of motion (like Gant, up above). Since the rules state that the bar needs to touch their torso in order to count, they get a little creative. Instead of bringing the bar down low, they can bring their torso up high. Their belly then meets the bar halfway, keeping their shoulders in a healthy position, improving their leverage and shortening the range of motion.

You’ll do better by keeping your back straight and simply stopping when your upper arms reach sufficient depth for optimal muscular development (parallel with the floor). You don’t want to drop it any further than that, as too much rotation in that joint will risk doing damage to it.

We’re of the belief that weightlifting should make you stronger, not weaker. Damage done to joints in the process of building bigger muscles doesn’t really fit with that objective.

One trick we use is rolling up a towel and putting it on our chests, simulating a larger ribcage. Even with your now-appropriately-thick-ribcage, you’ll still have a larger than average range of motion, since your arms are so long … and that’s actually pretty great news when it comes to building muscle. The more total work you do, the more growth you can stimulate.

Ectomorph Squatting

Squats are a tricky beast for us ectomorphs too, and by now you might be able to guess the fix. As you’ve probably heard a thousand times, the lower you squat the better. That’s true. Deep squats are one of the best ways of involving the biggest and most powerful muscle groups in your body. You’ll be building up your quads, hammies, calves, core, posterior chain, ego and glutes. The squat works over 200 muscles and it does a better job of training your abs than the plank does.

The benefits keep compounding the lower you can go with perfect form. The deeper you squat the more your gains will translate into hearty real world strength (study), the more glute activation you’ll get (study), and, since muscle hypertrophy is positively correlated with range of motion, the more muscle size you’ll build.

So deep squats are a badass lift, especially for us ectomorphs who are seriously eager to add some thickness to our bodies.

…But just because rockin’ out a deep squat rocks doesn’t mean that you should be doing them. At least not yet.

Many of these classic exercises are actually quite advanced. Moreover, couches, cars (buses, etc) and chairs are all notorious for reducing people’s ability to squat like champs.

So we’ve got to come clean about our athleticism (or lack thereof) and start where we’ve got to start. Exceed the mobility of your hips and all of a sudden you’re causing knee and lower back stress. You only get the benefits if you can execute the lift properly, and building up the hip mobility required to squat deep properly takes time and conscious effort. If your back is flailing around like a fish at the bottom of your squat, your knees are hurting, or your lower back is rounding over, you’re squatting too low.

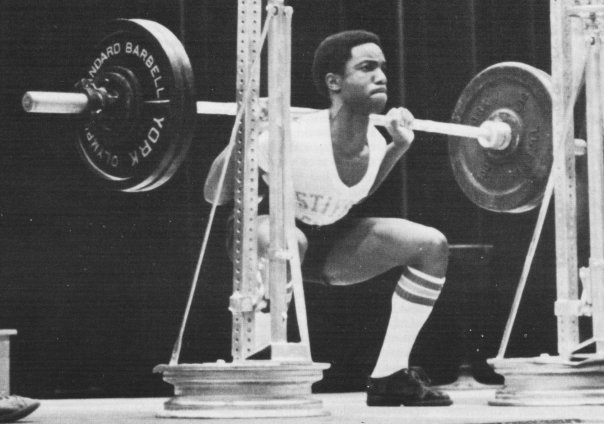

Like with his bench, Gant has a horrendous body for squatting. He’s got a tiny torso and enormous legs. #ectomorphproblems

To make up for it, he had to develop pretty unbelievable hip mobility in order to get to depth. But he did:

So as an ectomorph you should probably squat, and you should probably squat deep… eventually.

(One thing to keep in mind is that while the studies are all in agreement that the deeper you go the more muscle activation you’ll get, they also used the same load for the varying depths. That was an oversight. Obviously when you restrict range of motion you can haul heavier weights, so there are advantages and disadvantages to all ranges of motion that aren’t necessarily reflected in these studies. The heavier load you’d be able to handle with a reduced range of motion may make up for inferior squat depth. You can work with what you’ve got and build a whole helluva lot of muscle while also working on your depth.)

As for lifting safely, learning solid technique and building muscle every step of the way, keep leverages in mind. The further in front of you the load is, the more upright you’ll be able to keep your torso, and the less hip mobility you’ll need to do the lift safely. So start with goblet squats, then progress to front squats, and gradually work your way down deeper and deeper until maybe one day you’re comfortably past parallel when doing beautiful full back squats.

How to Lift as an Ectomorph

It’s pretty typical to be a little atypical. When it comes to any lift there’s always a chance that it won’t quite suit your body or your experience level. As someone who would call themselves thin, skinny or an ectomorph, it’s quite likely that’ll be the case for a good number of the lifts popular in the bodybuilding and strength training industries, as they’re dominated by stocky guys with decades of lifting experience.

That isn’t the case with weightlifting in general though, as many lifts are geared more towards athletes, and athletes come in all shapes and sizes. There’s plenty of research done into lifting with a wide variety of body types.

Whatever style of lifting you do, a good rule of thumb is that lifting should feel good. You shouldn’t feel pain in your joints, you shouldn’t feel pinches, and you shouldn’t be worried that a limb will pop off.

Lift with a weight that’s challenging yet comfortable and generally stay away from failure during your heavy sets—at least during your first few months of training. As a relatively untrained ectomorph looking to build size and strength you probably shouldn’t be squatting, deadlifting or benching to failure every week, if ever. That’s where form deteriorates, recovery times become enormous, and injuries become more common.

There are exceptions to every rule, but in general if anything it’s the littler and more isolated exercises, like bicep curls, that you’d want to risk going to failure on, not the big heavy compound strength and mobility builders.

Focus on the details of perfecting form when practicing and warming up; focus on lifting when you’re lifting. Our goal isn’t to turn you into a rigid lifting robot; you’re still supposed to lift like a rugged beast. Developing perfect textbook technique is something that happens over years of training, not before you ever do your first squat. There’s plenty of time to focus on perfecting your form while warming up and practicing your lifts. You can check yourself out in the mirror, hold a broomstick against your back to keep it straight, etc. When it comes time to actually lift weight though, it’s often easier to loosen up a bit and focus more on lifting “naturally”. Holding onto tension and getting too cerebral while lifting can often be more troublesome than just selecting a weight you’re totally in control of and then lifting it.

There’s no need to be lifting the most you absolutely can or forcing yourself through ranges of motions your body can’t own yet. Weightlifting isn’t about how much you can lift today, it’s about how much more you can lift tomorrow.